Ever stepped out of an air-conditioned building into a city street and felt like you’d walked into an oven? That’s exactly how I felt last week in New York City. This is known as the urban heat island (UHI) effect. It makes cities significantly warmer than their surrounding rural landscapes, particularly at night. Why does this happen, and what are cities doing about it?

The Science Behind the Sizzle:

The UHI effect is largely a byproduct of how we build our cities. Here’s a quick breakdown of the culprits:

- Dark Surfaces & Materials: Concrete, asphalt, and dark rooftops absorb and store vast amounts of solar radiation during the day. Unlike natural landscapes (think forests or water bodies) that reflect more sunlight and release moisture, these urban materials slowly re-emit that stored heat into the surrounding air, keeping temperatures elevated long after sunset.

- Lack of Vegetation: Trees and plants provide natural cooling through shade and a process called evapotranspiration (where they release water vapor, like sweating). Cities, with their limited green spaces, miss out on these vital cooling benefits. The apartment building where I live straddles a city block. On one side, it’s a tree-lined street that’s almost completely shaded. On the other side of the building, there aren’t any trees at all. The temperature difference between the two entrances is often 10 degrees or more.

- Urban Geometry: Tall buildings and narrow streets can create “urban canyons” that trap heat and block wind flow, preventing cooler air from circulating and dissipating trapped warmth.

- Waste Heat: All the human activity in a city – cars, factories, air conditioning units – generates a significant amount of waste heat, further contributing to the overall temperature rise.

The consequences of the UHI effect are serious: increased energy consumption (more AC means more power plants working overtime), elevated air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions, and significant health risks, especially for vulnerable populations, including heat-related illnesses and even fatalities. In the United States, heat is indeed the deadliest weather-related hazard, claiming more lives annually than other extreme weather events like hurricanes, floods, or tornadoes

Cities Taking Innovative Action:

The good news is that cities around the world are recognizing this challenge and implementing clever, innovative solutions to cool down from cool pavement surfaces to using plants as part of walls, roofs, corridors, and increased green spaces. Here are a few inspiring examples:

- Singapore: The “Garden City” Goes Further Singapore is a leader in green infrastructure. Beyond its lush parks, the city-state is integrating vegetation into buildings with impressive “green walls” and “sky gardens.” They’re also exploring district-level cooling systems, which are more energy-efficient than individual air conditioning units, and prioritizing science-based policies to reduce urban heat risks. Their commitment to planting millions of trees and creating numerous parks is paying off in tangible temperature reductions.

- Los Angeles, USA: Paving the Way with Cool Pavements Known for its expansive roadways, Los Angeles has been actively experimenting with “cool pavements.” These lighter-colored surfaces reflect more sunlight and absorb less heat than traditional asphalt, significantly reducing surface temperatures. The city has already coated over a million square feet of pavement with these innovative materials. It is also experimenting with applying this coating to rooftops as well.

- Rotterdam, Netherlands: Embracing Green Rooftops Rotterdam is literally building a cooler future from the top down. The city is actively promoting and implementing green rooftops on a massive scale, aiming to green over 900,000 square meters of rooftops. These vegetated roofs not only reduce ambient temperatures by acting as insulation and through evapotranspiration but also help with stormwater management.

- Medellín, Colombia: Cultivating Green Corridors Medellín has transformed its urban landscape by creating a network of 30 “green corridors.” These shaded routes, lined with thousands of native trees, palms, and other plants, offer cooler pathways for people to travel and gather, directly combating heatwaves and improving air quality.

- Paris, France: Creating “Cool Islands” Paris is tackling its urban heat with a strategic approach to “cool island” spaces. The city has identified and is creating 800 such spaces, including parks, water fountains, and public buildings like swimming pools and museums, which are significantly cooler than surrounding streets. They also have ambitious plans to plant 170,000 trees by 2026.

- Seville, Spain: A “Policy of Shade” In a city accustomed to scorching summers, Seville has adopted a “policy of shade.” This includes installing more awnings, planting 5,000 trees annually, switching to heat-reflective construction materials, and installing more public fountains – all aimed at providing respite from the intense heat.

These examples demonstrate that while the urban heat island effect is a significant challenge, it’s not insurmountable. By embracing a combination of green infrastructure, cool materials, and thoughtful urban design, cities worldwide are proving that a cooler, more livable urban future is within reach.

What can you do?

Even as individuals, we can contribute to mitigating the UHI effect. Consider:

- Support local initiatives for tree planting and green spaces.

- Call your reps and offer these examples as something your city could try.

- Choose lighter-colored materials for your own property if applicable.

- Advocate for sustainable urban planning in your community.

Let’s work together to make our cities cooler, healthier, and more sustainable for everyone!

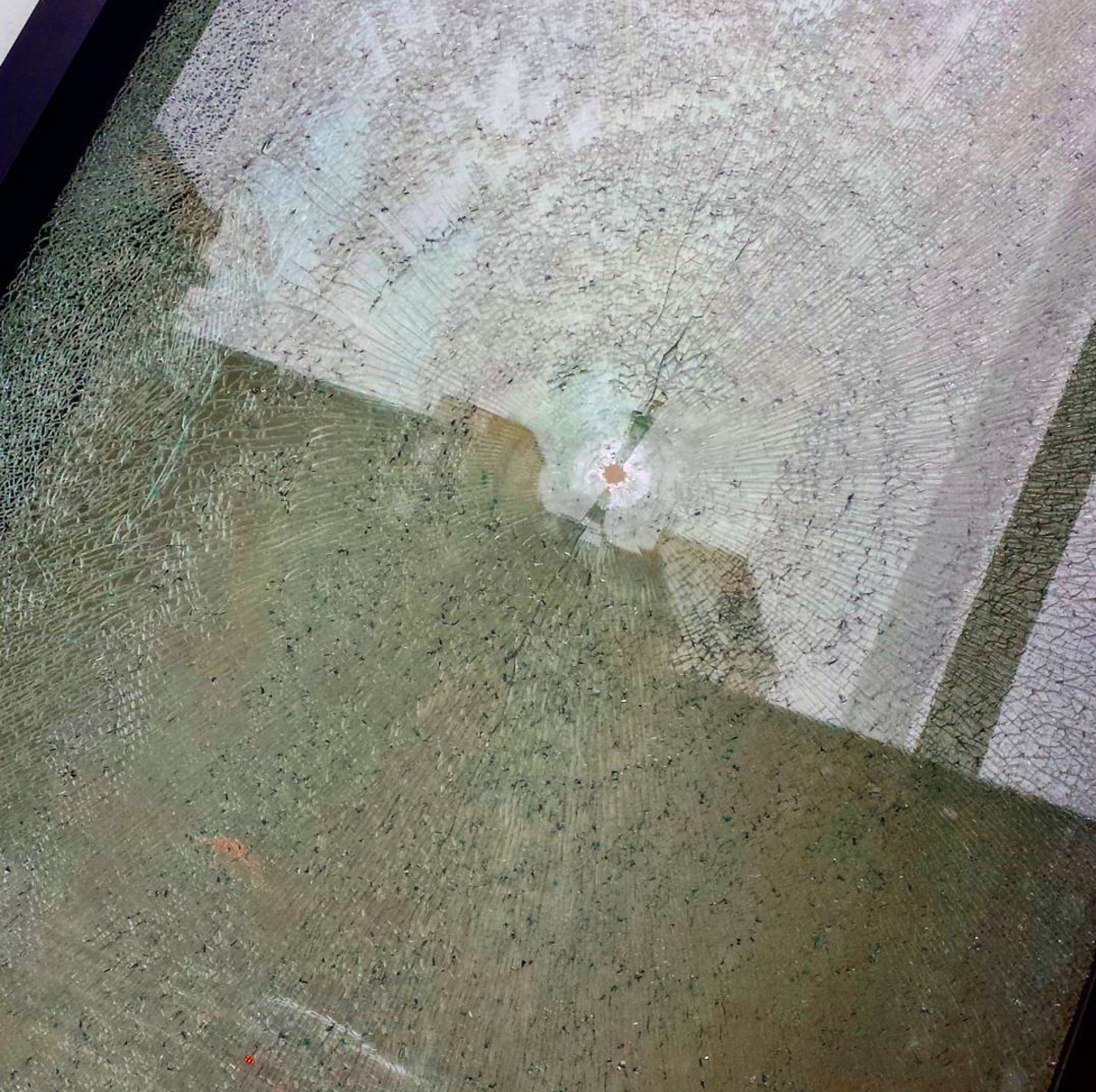

That’s a bullet hole in the middle of a shattered window in my apartment building lobby. According to the DC Police Department, it was caused by an assault rifle, a military-grade weapon. By law, these weapons cannot be owned in D.C. by any civilian for any reason, meaning the weapon was stolen or sold illegally. The reflection in the window is the building across the street, one of the largest public housing complexes in the city, and the stage for that gun fight. The irony

That’s a bullet hole in the middle of a shattered window in my apartment building lobby. According to the DC Police Department, it was caused by an assault rifle, a military-grade weapon. By law, these weapons cannot be owned in D.C. by any civilian for any reason, meaning the weapon was stolen or sold illegally. The reflection in the window is the building across the street, one of the largest public housing complexes in the city, and the stage for that gun fight. The irony